Some conflicting information has been floating around about BMI (Body Mass Index). Some say it’s not important and just used by those who seek to fat- or skinny-shame individuals, yet doctors continue to use it flags in some healthcare assessments. Just how accurate is BMI? Should it be used as a

weight-loss tracker? What information can you trust?

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a calculation using a person’s weight and height. The exact formula is [weight in kilograms] divided by [height in meters]. BMI applies to most adults aged

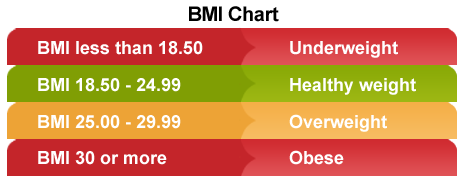

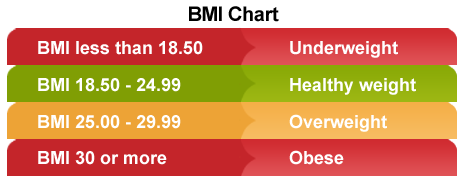

18 to 65. While BMI doesn’t measure body fat directly, research has shown that BMI is correlated with other, more direct measures of body fat, such as skinfold thickness measurements and underwater weighing. As a whole, however, BMI is an inexpensive and easy-to-use method of discovering an individual’s weight category. The categories are listed below:

According to the Dieticians of Canada, BMI is one of various factors that your healthcare provider uses for assessment

[1]. For individuals who are very heavy, normal BMI provides a weight-loss goal to aim for. BMI categories also help healthcare providers to recognize those with low BMIs who may have an eating disorder, or those with high BMIs who may be at risk for complications

[2].

The Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification of Adults includes BMI as well as WC (waist circumference)

[3].

Although it’s a useful tool, it isn’t right for everyone. It may not be able to accurately assess health risks in: muscular athletes, individuals under 18 years, women who are pregnant or lactating (breastfeeding) or adults over 65

[1]. The Canadian Diabetes Association posits that BMI can’t assess these kinds of individuals because it does not account for whether the weight carried on a person is muscle or fat; it just indicates the number. Therefore, those with a high muscle mass may show up as

overweight or obese on a BMI chart, but could be perfectly healthy.

On the other side of the spectrum, those with low muscle mass, like children under 18 or adults over 65 might also have a lower BMI than indicated

[4]. For children and

teens in particular, although BMI can be used via the same calculation, age and sex need to be specified as body fat changes with age

[5]. Adults over 65 may be losing muscle mass, and BMI won’t reflect that. During pregnancy, the body composition changes vastly, so BMI would be inappropriate to use

[4].

In addition, factors such as age, sex and ethnicity aren’t accounted for in BMI for adults. Because it doesn’t measure body fat directly, BMI is not used as a diagnostic tool. To determine if an individual is at risk for complications, a healthcare provider would also need to look at: skinfold thickness measurements, evaluation of diet, physical activity and family history of certain conditions

[6]. BMI can also be used to track weight status on

population groups and as a way to identify potential weight problems in individuals

[7]. Although the correlation between BMI and body fat exists, even if two people have the same BMI, their body fat percentages can differ

[5].

There are various risks that come with BMIs that are not in the normal range. Overweight and obese individuals are at risk for health complications such as: high blood pressure, high LDL cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease and osteoarthritis. Those underweight are at risk for: anemia, hair loss, fertility issues (for females) and a weakened immune system

[8]. BMI should not be confused with BMR, the Basal Metabolic Rate, which indicates the amount of daily calories your body would burn if you slept all day. Unlike BMI, BMR is age and sex-specific, and

decreases as you age [9].

Getting the right information about your health and weight is important when it comes to making changes, so while the Internet is a nice place to start, always check with your doctor if you’re not sure.

According to the Dieticians of Canada, BMI is one of various factors that your healthcare provider uses for assessment [1]. For individuals who are very heavy, normal BMI provides a weight-loss goal to aim for. BMI categories also help healthcare providers to recognize those with low BMIs who may have an eating disorder, or those with high BMIs who may be at risk for complications [2]. The Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification of Adults includes BMI as well as WC (waist circumference) [3].

According to the Dieticians of Canada, BMI is one of various factors that your healthcare provider uses for assessment [1]. For individuals who are very heavy, normal BMI provides a weight-loss goal to aim for. BMI categories also help healthcare providers to recognize those with low BMIs who may have an eating disorder, or those with high BMIs who may be at risk for complications [2]. The Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification of Adults includes BMI as well as WC (waist circumference) [3].

On the other side of the spectrum, those with low muscle mass, like children under 18 or adults over 65 might also have a lower BMI than indicated [4]. For children and teens in particular, although BMI can be used via the same calculation, age and sex need to be specified as body fat changes with age [5]. Adults over 65 may be losing muscle mass, and BMI won’t reflect that. During pregnancy, the body composition changes vastly, so BMI would be inappropriate to use [4].

On the other side of the spectrum, those with low muscle mass, like children under 18 or adults over 65 might also have a lower BMI than indicated [4]. For children and teens in particular, although BMI can be used via the same calculation, age and sex need to be specified as body fat changes with age [5]. Adults over 65 may be losing muscle mass, and BMI won’t reflect that. During pregnancy, the body composition changes vastly, so BMI would be inappropriate to use [4].

There are various risks that come with BMIs that are not in the normal range. Overweight and obese individuals are at risk for health complications such as: high blood pressure, high LDL cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease and osteoarthritis. Those underweight are at risk for: anemia, hair loss, fertility issues (for females) and a weakened immune system [8]. BMI should not be confused with BMR, the Basal Metabolic Rate, which indicates the amount of daily calories your body would burn if you slept all day. Unlike BMI, BMR is age and sex-specific, and decreases as you age [9].

There are various risks that come with BMIs that are not in the normal range. Overweight and obese individuals are at risk for health complications such as: high blood pressure, high LDL cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease and osteoarthritis. Those underweight are at risk for: anemia, hair loss, fertility issues (for females) and a weakened immune system [8]. BMI should not be confused with BMR, the Basal Metabolic Rate, which indicates the amount of daily calories your body would burn if you slept all day. Unlike BMI, BMR is age and sex-specific, and decreases as you age [9].